Chapters to Malcolm’s unpublished book

Click on the chapter title to download a PDF file.

Introduction

Chapter One: DISHONESTY THE ONLY POLICY

CHAPTER TWO: DESCRIBING THE SINGLE TRANSFERABLE VOTE

Chapter Three: A BRIEF HISTORY OF SENATE VOTING

Chapter Five: Increasing the size of Parliament

CHAPTER SIX: THE PREFERENCE WHISPERER

Chapter Seven: EXTREME VETTING

CHAPTER EIGHT: REFORM OF UPPER HOUSES IN NEW SOUTH WALES AND SOUTH AUSTRALIA

CHAPTER NINE: CLARK AND SPENCE

Chapter ELEVEN: judges exercise their power

Chapter Twelve: The Senate as Unrepresentative Swill

Conclusion

obituary for bogey musidlak

UNREPRESENTATIVE SWILL: Australia’s Ugly Senate Voting System

Introduction

There have been few masters of invective in Australia’s recent political history but one of them most surely was Labor’s Paul Keating who served as Prime Minister from 20 December 1991 to 11 March 1996, a period of four years, two months and 24 days. His Treasurer was John Dawkins and during question time in the House of Representatives on Wednesday 4 November 1992 questions were being asked about whether Dawkins should appear before the Senate Estimates Committee. Addressing the then Leader of the Opposition, John Hewson, and the then Liberal member for Mayo, Alexander Downer, this is what Keating had to say:

You want a Minister from the House of Representatives chamber to wander over to the unrepresentative chamber to account for himself. You have got to be joking. Whether the Treasurer wished to go there or not, I would forbid him going to the Senate to account to the unrepresentative swill over there.

After some interjections Keating continued:

You are into a political stunt. There will be no House of Representatives Minister appearing before a Senate committee of any kind while ever I am Prime Minister, I can assure you.

All the details are there on page 2549 of Hansard for that day. Journalists immediately went to work on Keating’s language. They discovered that the Macquarie Dictionary defined “swill” as “liquid or partly liquid food for animals, especially kitchen refuse given to pigs.”

Of all the colourful phrases invented by Keating the one that has defined him the most would surely be “unrepresentative swill” as a description of the Senate. I agree with Keating on his description of the Senate – but not with his reasoning. The main reason why Keating (and several other former Labor federal ministers) disparage the Senate is because of the malapportionment of its electoral base. When New South Wales has fifteen electors for every Tasmanian elector it is a malapportionment that they should both have the same number of senators. That is why Labor people so often think of the Senate as unrepresentative swill. In the case of the specific quotation above it reflected also Keating’s annoyance at the situation he was in. He lacked Senate numbers!

By way of contrast I think of the malapportionment as merely reflecting the federal nature of Australia’s Constitution. On the Labor way of thinking the Senate problem could only be fixed by a referendum that would be impossible to carry. I think otherwise. The Senate problem can be fixed by giving the Australian people a decent Senate voting system. That can easily be done by the politicians implementing electoral reform. That can be done by simple legislation.

The present Senate electoral system is unfair to voters, unfair between parties and unfair between candidates. The democratic reforms I propose would make it fair to voters by doing away with the contrivances of the present ballot paper which are there for the purpose of manipulating voters. My reforms would make it fair between parties by increasing the number elected at a half-Senate election for states from six to seven. My reforms would add to that fairness by increasing the number elected from each territory from two to three. Furthermore, my reforms would make the system fair between candidates by doing away with above-the-line voting.

The present system was touted as being a “democratic reform” when it was implemented courtesy of the Commonwealth Electoral Amendment Act 2016 which passed through both houses of federal parliament in the autumn of 2016 in time for the double dissolution general election of July 2016. The claims made on its behalf were totally lacking in substance. This system is nothing more than a thoroughly dishonest re-contriving of the contrivances of the former system. It was implemented in the most cynical way it would be possible to imagine.

A brief history of Senate voting

There have been six Senate voting systems since Federation. In my opinion only one has been reasonably satisfactory, namely the Single Transferable Vote system of proportional representation introduced by the Chifley Labor government in 1948. It applied at Senate elections from December 1949 to March 1983.

There is a problem with this book that I must acknowledge straight away. The original was four times the size of this. It was unpublishable in the sense that its size made it too unprofitable for publishers. I have made it publishable by setting up a website to which reference is made throughout this essay. The website is titled “Unrepresentative Swill” and can be accessed at www.malcolmmackerras.com.

The first chapter of the magnum opus is titled “A brief history of Senate Voting”. It comes to nine thousand words. The table attached to it is the same as here. It deals with that perpetual bugbear of the Senate electoral system – its high informal vote. In doing so it lists the six voting systems to which reference is made above. The table also lists the names of the systems.

The first three methods were “winner takes all” systems. I give their names and dates in passing. The first I call “multi-seat plurality”. It applied at elections from 1901 to 1917. The second I call “preferential block majority – partial optional preferences”, applying from 1919 to 1931. The third I call “preferential block majority – compulsory preferences” applying from 1934 to 1946. Fifty years of those systems frequently gave Australia a lop-sided Senate. Thus, for example, during the years 1947, 1948 and 1949 the Chifley government had a huge Senate majority with there being 33 Labor senators and just three from the Opposition, two Liberals and one from the Country Party.

At that time there were 36 senators (six from each of six states) and 74 full-voting members of the House of Representatives plus one member for the Northern Territory who did not enjoy full voting rights. The Chifley legislation increased the number of senators from 36 to 60. As a consequence, the size of the House of Representatives increased to 121 full voting members plus one each for the two territories, both denied full voting rights but the total, nevertheless, was 123 members fitting into the House of Representatives chamber compared with 75 while Ben Chifley was prime minister.

The changes from the first to the second system and from the second to the third were made to strengthen the short-term electoral prospects of the party in power, in both cases a conservative party. However, this much should be noted. Both in 1919 and in 1934 there were strong voices who asserted that the system should not be “winner takes all” but should be according to the principle of proportional representation (PR).

That was a case of the politicians speaking. Perhaps more important was that, in August 1927, the Bruce-Page government appointed a Royal Commission of Inquiry into the Constitution. It recommended PR.

The 1934 reform began the situation whereby, to record a formal vote, the elector was required to number all the candidates on the ballot paper in consecutive order. That constraint upon the will of the voter applied at all elections from September 1934 to March 1983. In the 1934 debate Labor Senator Arthur Rae (NSW) predicted that the informal vote would rise. A look at Statistical Appendix Table 1 indicates that he was proved right. The Senate informal percentages were 8.6 in 1919, 9.4 in 1922, an even 7 in 1925, 9.9 in 1928 and 9.6 in 1931, an average of 8.9 per cent. Under the new system the informal percentages were 11.3 in 1934, 10.6 in 1937, 9.6 in 1940, 9.7 in 1943 and an even 8 in 1946, an average of 9.8 per cent.

A non-contentious change was made in 1940 when the Act was amended so that groups of candidates could choose the order in which names of candidates were listed on the ballot paper. The ordering of the groups in future was to be done by ballot rather than alphabetically as was previously the case. Ungrouped candidates were likewise ordered by ballot. Candidates were grouped in columns for the first time, the order being determined by agreement. What this meant was that, from 1940 to the present day, the party machine has decided the rank order of the party’s candidates.

Proportional representation – the genuinely democratic STV system (1949-83)

To Ben Chifley owes the title of prime minister when the only real, genuinely democratic, reform was made to the Senate electoral system. The new system was passed through parliament in 1948. From the start it was correctly known as “proportional representation by means of the single transferable vote” (PR-STV). This radical change occurred in the context of the expansion of the parliament’s size. The so-called “nexus” provision of section 24 of the Constitution applied. It provides that the number of members of the House of Representatives shall be, as nearly as practicable, twice the number of senators. It was, therefore, logical to add 24 senators (from 36 to 60) and simultaneously add 48 members of the House of Representatives (from 75 to 123.)

Two features of Labor’s decision-making were surprising. The first was that Labor could get away with such a massive increase in the number of politicians. The second was that Labor would decide to keep the requirement that voters must rank all candidates consecutively to record a formal vote. The explanation for the first surprise is that there was widespread agreement that it be done. The explanation for the second is given later in this essay.

The Senate election in 1949 was for seven senators in each state, with five having long terms and two having short terms, those latter joining the three elected in 1946. Since Labor had 15 of those 18 it meant Labor could not lose its Senate majority. That fact was the reason why a double dissolution of the 1949-51 parliament (the 19th Parliament) was widely seen at the time to be highly likely if the Coalition parties were to win government, as they did with Robert Menzies as prime minister. Sure enough, there was a double dissolution in March 1951 with general elections for all members of both houses in April. All 60 senators and all 123 members of the House of Representatives required re-election on Saturday 28 April 1951. Menzies won majorities in both houses.

In re-establishing the rotation of senators following a double dissolution, the Constitution back-dates the beginning of a new term. Under section 13 the new term normally begins on 1 July following a senator’s election but, following a double dissolution, “it shall be taken to begin on the first day of July preceding the day of his election.” So, in each state five senators enjoyed terms expiring on 30 June 1956 and five had terms expiring on 30 June 1953.

In May 1953, therefore, there was a separate periodical election for half the Senate, the first case of that occurring separate from the general election for the House of Representatives in the history of the Commonwealth. The number of electors who voted in New South Wales was 1,873,521 and the informal vote was 74,231, a mere four per cent. Labor won three seats and the Liberals two. Labor was not complaining then.

Fast forward twenty-one years and there was a double dissolution election in May 1974. In New South Wales there were 73 Senate candidates, the number voting was 2,702, 903 and the informal vote was 332,818 or 12.3 per cent, triple the 1953 percentage. Labor was now complaining loudly. The result was 5-5 between Labor and the Coalition. A variety of election analysts agreed that, but for the high informal vote the result would have been 6-4 in Labor’s favour.

First the Whitlam government and then the Hawke government tried to reduce the informal vote by limiting the requirement on the elector merely to numbering squares on the ballot paper up to the number to be elected. That is what I now propose. However, the Coalition parties would not have a bar of that, so Senate majorities were not there to implement such a proposal.

Before I proceed to describe how the Hawke Senate voting system replaced that of Chifley, I should mention that the first four were candidate-based systems. They clearly complied with the requirement of section 7 of the Constitution that senators shall be directly chosen by the people. There were deficiencies in the first three “winner takes all” systems – which is why they were scrapped. However, they were genuinely systems of direct election.

The Chifley system was the best because it combined direct election with PR. The only thing wrong with it was the requirement of numbering every square. That could have been easily fixed. It was not fixed due to politics – explained later in this essay.

Proportional representation in stasiocratic form (1984-2014)

Above-the-line voting is the characteristic common to the Hawke system (1984-2014) and the present Turnbull system (since 2016). In its original form it is was justified as the only politically realistic way in which the informal vote could be reduced. I accepted that argument at the time of the 1983-84 debate – and for a few years afterwards. However, during the period of its operation I came, in an intellectual exercise, to my present view which is that above-the-line voting is both undemocratic and unconstitutional.

Above-the-line voting is stasiocratic, a system over which the party machines have a firm grip. I don’t know where the term “stasiocracy” comes from, but it is a useful term meaning simply “government by party machines”. “Democracy” means “government of the people, by the people and for the people.” The Australian Constitution has democratic values. Both senators (section 7) and members of the House of Representatives (section 24) shall be “directly chosen by the people”. That requires both senators and representatives to be elected in candidate-based electoral systems.

Before I go on to describe the Labor Party’s (Hawke) system I should reveal that I have had difficulty deciding on a name for this method. I have decided on this: “Stasiocratic STV in First Unconstitutional camel”. A camel is an animal designed by a committee so that word is appropriate. This system, like its successor, was designed by a committee of politicians pursuing the short-term electoral interests of the party machines that gave them their seats. Therefore, it was a camel.

However, I defended Hawke’s stasiocratic system from start to finish. I defended it on grounds that it provided a voter-friendly ballot paper, would substantially reduce the informal vote, would distribute seats fairly between parties, and produce good government. It did all those things during its thirty years of operation.

But, what about the Constitution’s requirement of direct election? What about fairness between candidates? On the former I argued that if the High Court were willing to accept the proposition that the system complied with the Constitution then so should I. Further, I argued it did not matter that it was unfair between candidates. All that mattered was that it be fair between parties.

Electoral system questions are all about acceptance. If a system is accepted, it lasts. Otherwise, it is scrapped. So, what about Hawke’s stasiocratic system? It appeared to be accepted over a thirty-year period – but it never was accepted. The Proportional Representation Society of Australia (PRSA) never accepted it – and it did not take me very long to understand that the PRSA leaders thoroughly disapproved of my defence of the Hawke system. I quickly realised why they always had (and still have) this view: ALL FORMS OF ABOVE-THE-LINE VOTING SHOULD BE ABOLISHED. I have taken those words from a letter I received from them many years ago. The words are there underlined in bold lettering that are as black as the Ace of Spades.

The worst feature of Hawke’s system was something that was not properly understood at the time it began. It gave the machines of big political parties a sense of entitlement. Henceforth they could defeat a “rogue” big-party senator by dumping that senator to an unwinnable position on the ticket. It is pure greed for the machines of big political parties to think they have the right to do that. But the fact that High Court judges would allow a party machine appointments system like that to pretend senators are directly chosen by the people gave those machines their sense of entitlement. The big party machines acquired the illegitimate power to do that through Hawke’s above-the-line voting system.

There is an important difference between these two dishonest systems. The Hawke system did not seem to be dishonest. By contrast it is very easy to explain to ordinary people that the Turnbull system is dishonest. It will collapse before too long. Its life span will be shorter than that enjoyed by the Hawke system.

Voter-manipulative proportional representation begins in 2016

Having decided to describe the Labor Party’s (Hawke) system as “Stasiocratic STV in First Unconstitutional Camel” it follows logically that I should call the Liberal Party’s (Turnbull) system “Manipulative STV in Second Unconstitutional Camel”.

Technically the Turnbull system began with the 8th Senate general election held in July 2016 following a double dissolution. However, that is not the way in which I think of it. Rather I think it began in the 46th Parliament, Scott Morrison’s Parliament, elected in May 2019. I say that because the Senate state of parties in the 46th Parliament has been determined by half-Senate elections from July 2016 and May 2019. From this state of parties can be seen the cunning design of the system. It was not designed to help voters. It was designed to contain, preferably eliminate, minor parties. It was also designed to deal with “rogue” Liberal senators.

For these reasons it is the worst of the six systems. The Hawke system, occasioned by a desire to bring about the second enlargement of the House of Representatives, had no such restrictions. Its purpose was voter convenience. It was very unfortunate that such an operation had to be done in that way, my only objection to it at the time it began. There is also another aspect to Hawke’s system. By increasing district magnitude from five to six at normal half-Senate elections and from ten to twelve at Senate general elections, it helped minor parties – even though that was not the purpose of the new system. “District magnitude” is psephological jargon for the number to be elected. Thus, it is one for the House of Representatives, five for normal half-Senate elections under the Chifley system, six at present and seven at the 1949 election, the first under the Chifley system. It was also seven at the 1984 election, the first under the Hawke system. It is presently five for the two Hare-Clark systems and five for the system whereby the Victorian Legislative Council is elected. It is 21 for the NSW Legislative Council and 11 for the South Australian Legislative Council. For Western Australia it has been six under the failed old system that last operated in March 2021. It will be 37 at the new system which is a genuine democratic reform and will operate first in March 2025. That increase will produce a genuinely proportional result in 2025. Indeed, WA Legislative Council elections will, in future, always produce the most proportional results in the country.

Towards the Autumn 2022 Federal Election

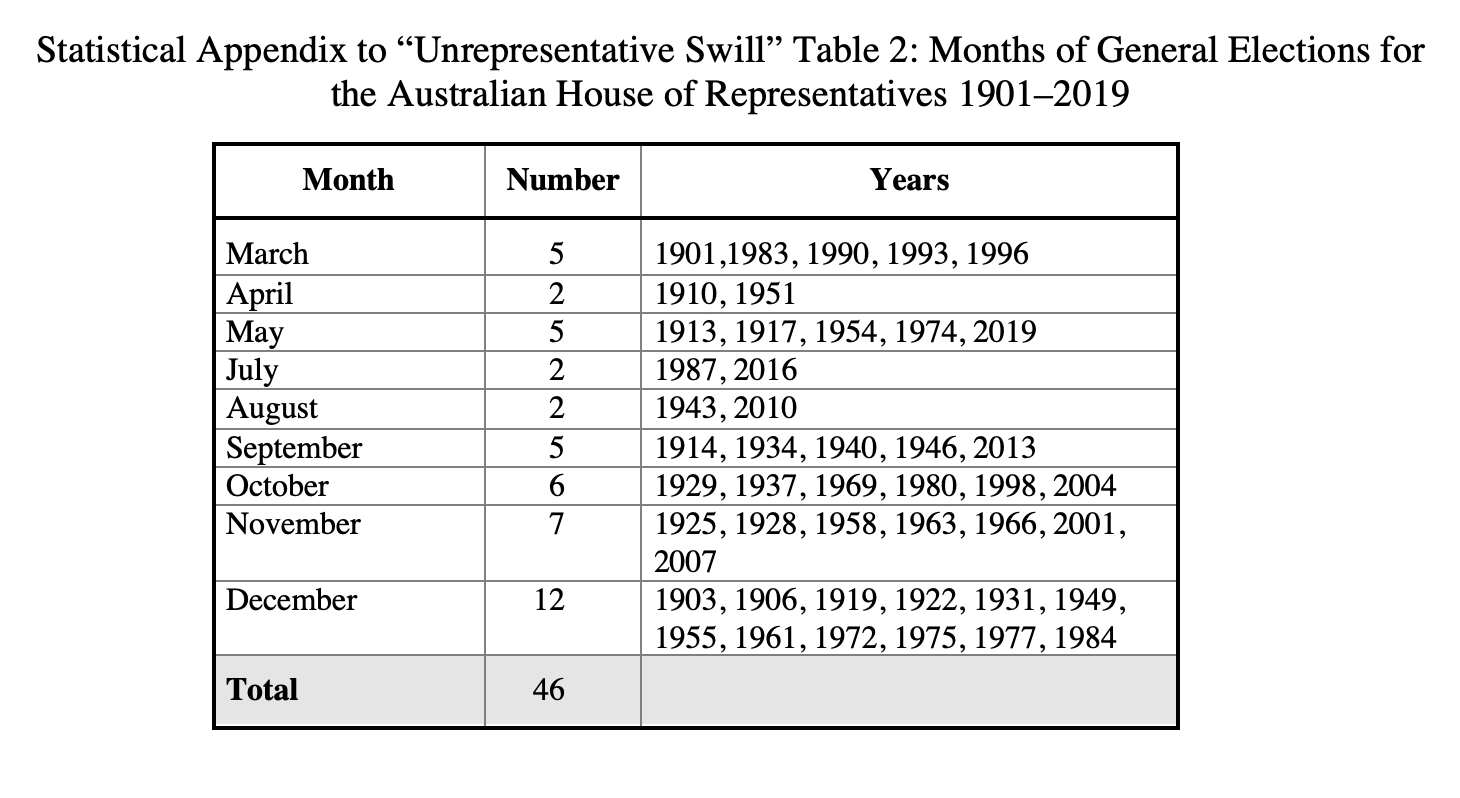

The forthcoming election will be “normal” in the sense that it will be for the House of Representatives and half the Senate. I believe its date will also be normal. But what is normal? The answer to my question is given in Statistical Appendix Table 2 which gives the history of the choice of date. The most normal date would be Saturday 27 November 2021. Note this detail: the election latest in the calendar year was held on 19 December 1931. Two other elections were held late in December, on 16 December 1903 and 16 December 1922. All other December elections were held in the first half of the month. However, according to a different criterion of normality the next federal election will be held on Saturday 21 May 2022.

Nevertheless, there are peculiarities in the present political situation. These peculiarities, in my opinion, guarantee that the election will be held no earlier than 5 March 2022 and no later than 21 May 2022. That being so it is wholly sensible to refer to the “autumn 2022 federal election”.

Normal Australian elections see a great concentration of media attention on the House of Representatives – and very little on the Senate. Recent exceptional cases, however, have been the half-Senate election in September 2013 and the Senate general election of July 2016. Those Senate elections attracted unusual interest due to an expectation that a high vote for “Other” candidates would produce a sizable Senate cross bench. The expectation proved correct in both cases. In 2013 Clive Palmer was the beneficiary of the high “Other” vote. In 2016 Pauline Hanson was the big winner from that vote.

The May 2019 half-Senate election produced a predictable result. I predicted the correct result in every jurisdiction except Victoria where I was doubtful to the end. The autumn 2022 election will again produce a predictable result but – as in May 2019 – I reserve my right to be doubtful about one state, Queensland.

Here are my predictions. As always, the territories will split one-one in each so the states are the electorates that matter. In New South Wales the result will be three Coalition, two Labor, one Greens. That compares with three each in July 2016 between Coalition and Labor. In Victoria the result will be three Coalition, two Labor, one Greens, the same as in 2016. In Western Australia it will be three Liberal, two Labor, one Greens, the same as in 2016 and in Tasmania it will also be three Liberal, two Labor, one Greens, again the same as in 2016.

At this point my reader may wonder about my reference to 2016 half-Senate elections. Was not 2016 a double dissolution election? Yes, it was, but at a Senate general election there is also a half-Senate election. It takes the form of a Senate resolution giving certain senators six-year terms. The result of that election in 2016 is shown in my Statistical Appendix Table 7. In conducting that election pursuant to section 13 of the Constitution the Senate gave six-year terms to seventeen Coalition senators, thirteen Labor, three Greens, two from Nick Xenophon’s Team and Pauline Hanson. Further details can be seen in my Statistical Appendix Table 9.

So, an interesting case in 2022 will be South Australia. In 2016 the SA half-Senate election gave two Liberal senators, two Labor senators plus Nick Xenophon and Stirling Griff (of what is now “Centre Alliance”) wins of six-year terms, the above-named having been the first six elected at the 2016 double dissolution election. Xenophon has been replaced by Rex Patrick who has now decided his only chance of re-election is to be an independent. I cannot see either Griff or Patrick winning again. If Xenophon stands again, he might be elected – but the odds would be against him. That being so I predict the result will be three Liberal, two Labor, one Greens. In the very unlikely event of Griff or Patrick winning it would be Patrick whose win would be at the expense of the Liberal Party. If Xenophon wins it would be Xenophon at the expense of the Liberal Party.

Now, suppose the result in Queensland is three Liberal National Party, two Labor and Pauline Hanson (the same result as at the 2016 half-Senate election) the effect would be to see the total Coalition number rise from 36 to 37 senators. The Coalition’s percentage of senators, therefore, would rise from 47.4 per cent to 48.7 per cent of seats, won on a vote of 38 per cent in 2019 and, presumably, about 38 per cent in 2021. The over-representation of the Coalition (seats versus votes) would be about ten per cent.

The statistics are all to be found in the third, fourth, fifth, sixth, seventh, eighth, ninth and tenth tables of my Statistical Appendix. They leave no doubt about the truth of the Commonwealth Electoral Amendment Act 2016. It was not a genuine “democratic reform” as claimed by its supporters. It was a thoroughly dishonest re-contriving of the contrivances of the immediate past system, implemented in the most cynical way it would be possible to imagine. It was a Liberal Party rig from the start but brilliantly executed by the Liberal Party’s machine, having gained support from the Nationals, the Greens and Senator Nick Xenophon. Just as important, perhaps, was the fact that distinguished psephologists like Antony Green, Kevin Bonham and George Williams strongly supported this “democratic reform” designed to rid the cross bench of as many senators as the Liberal Party-Greens Faustian pact could engineer. It is a disgrace – a blot on the landscape of Australian democracy.

Coalition strategists have plotted that the above should be the result – but it may go wrong for them. There is a fifty per cent chance that the result in Queensland will be two each for LNP and Labor with one seat each going to the Greens and Pauline Hanson. Were that to be the case the Coalition numbers would stay at 36, the Liberal Party’s gain of a seat in South Australia (in effect Xenophon’s old seat) being offset by the Liberal Party seeing Queenslander Amanda Stoker defeated from third LNP position and her seat going to the Greens.

Suppose that happens and there is a Labor government with Anthony Albanese as prime minister. That Labor government would find itself supported by a maximum of 38 senators (Labor plus Greens plus Jacquie Lambie) but opposed by 38 senators (36 Coalition plus Hanson and Roberts). The media description of such an outcome would be that Hanson and Roberts hold the balance of power.

There is one detail of the Queensland Senate election about which I am quite confident to predict. Former Queensland LNP Premier Campbell Newman will stand for the Liberal Democrats but will not be elected. Consequently, he will not hold the balance of power.

Manipulating the voters

“The people are not there to be served, nor are they there to be helped. The people are there to be manipulated.” Such is the mantra upon which apparatchiks of Australia’s party machines operate. It is the same the world over – in democracies at least. For at least ten years (and probably for much longer) Australia’s Commonwealth Parliament has been run by the big party machines, operating under that concept. The politicians put there by the machines no doubt claim to espouse “democratic principles” when they agree to (or resist) a “reform.” More often than not, however, those “principles” are concocted by the parties to suit their own short-term electoral interests and strategies. We know American politicians think like that with their infamous gerrymandering, which one of their Founding Fathers invented. Australia’s federal politicians play the same kind of tricks when they introduce upper house systems of proportional representation that they have continually been changing to expedite ever more substantial stage-management of the process. All the above sounds cynical – but I have been operating in this industry for sixty-five years. Those years have taught me to be very cynical.

Liberal party machine owns the system – and drafted the ballot paper wording

Since the Liberal Party foisted this system on the Australian people in 2016 (with Senate numbers given to the Liberals by adding the Nationals, Greens and Xenophon) I have given many talks and had many conversations with people on this subject. I begin by showing a typical Senate ballot paper or, if I do’nt have one on me, I tell the listener about it. The example I have taken here comes from the election of six senators from New South Wales in May 2019, an election that produced the predictable election of Hollie Hughes, Andrew Bragg and Perin Davey from the Coalition, Tony Sheldon and Tim Ayres from Labor and Mehreen Faruqi from the Greens.

Here is shown the left-hand one-eighth of the ballot paper. You read the words “one-eighth” correctly: the ballot paper is very long – and very voter-unfriendly.

Having shown that ballot paper to my listener I then ask him or her to guess the purpose of the wording. Invariably I get an answer that is unsatisfactory or, at best, semi-satisfactory. I then suggest this: “the purpose of the wording of those instructions is to deceive the voter into believing that any failure to number the boxes 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 and 6 above the line (or 1 to 12 below the line) would result in that ballot paper being placed in the pile of informal votes”. The listener then tells me that such is the assumption made by her/him and by voters generally. To which I say “that is what you are meant to believe but that is not true. A single first preference for a party above line thick black line is required by law to be counted as a first preference for that party. Thus, the voter who places the number”1” in the Coalition’s box is read as though voting 1 for Hollie Hughes, 2 for Andrew Bragg, 3 for Perin Davey, 4 for Jim Molan, 5 for Sam Farraway and 6 for Michael Feneley.

The voter who decided to do that preferential vote between candidates (rather than vote above the line) would also cast a formal vote required by law to be counted as a formal vote. You don’t need to number twelve squares below the line. Six is enough for a formal vote.

From that point onwards (after insisting that I am telling the truth, for voters find this hard to believe) I have no difficulty persuading the listener that this system is thoroughly dishonest as well as designed to manipulate voters. At no time have I needed to explain that the ballot paper is voter unfriendly. That is obvious to all without me needing to say so. I do, however, need to explain that the ballot paper is party machine friendly on steroids. So, let me now describe the election to which the above ballot paper applied.

The quota for election was 670,761 votes. The total formal vote was 4,695,326 of which 1,810,121 was for the Coalition (38.6 per cent) and 1,400,295 was for Labor (29.8 per cent). Within the Coalition the votes begin with the lead candidate, Hollie Hughes, who scored 1,664,188 votes of which 28,336 were cast below the line. The remaining votes were 2,533 first preferences for Andrew Bragg (elected), 3,030 for Perin Davey (elected), 137,325 for Senator Molan (defeated), 959 for Sam Farraway (not elected) and 2,086 for Michael Feneley (not elected).

So, Molan scored 54 first preference votes for every one first preference vote for Bragg and 45 such votes for every Davey vote. Molan was the highest-ranked former military commander to enter any Australian house of parliament for sixty years. He stopped the asylum seeker boats as Tony Abbott’s on water commander. His qualifications, however, were of no use to him under this party machine appointments system. The machine did not want him. It defeated him. Yet the sickening description of the result is that Bragg and Davey were declared “directly chosen by the people” with an official statistical return asserting each won 670,761 popular votes. On the other hand the same official statistical return declared that Molan was rejected by the people.

Soon after Molan’s defeat Liberal Senator Arthur Sinodinos resigned his seat to become Australia’s Ambassador to the United States. On Sunday 10 November 2019, therefore, the party’s NSW Council met in Sydney and, by 321 votes for Molan to 260 for the losing candidate, the 581 delegates chose Molan for the casual vacancy. He agreed to stand down at the next election, meaning his term would expire on 30 June 2022. He was given a consolation prize! Under any half-decent candidate-based voting system, however, he would have been elected to a full six-year term expiring on 30 June 2025. The Parliament of New South Wales chose him for the vacancy on Thursday 14 November and he returned to the Senate on Monday 25 November. My view on all that was expressed in Switzer Daily on Wednesday 13 November under the self-explanatory title: “Three cheers for Senator Jim Molan”. I noted, among other things, that 137,325 first preference votes from ordinary people were insufficient under the Liberal Party’s Senate electoral system to make him an elected senator, but 321 votes from party activists made him an appointed senator.

There are people in the Liberal Party who object to me referring to “the machine” when the selection committee was quite large – with some 600 party members able to participate. This is my response. On the first occasion I met Molan, in his Senate office on Monday 2 December 2019, he told me the whole story of his becoming a senator. He told me that the original committee, in early 2016, had only 108 members. That committee placed him in the unwinnable fourth position when the election was expected to be for half the Senate late in 2016. When that expected half-Senate election expanded to a full-Senate election the party’s State Executive decided he should be given the unwinnable seventh place for the July 2016 poll. That the size of the Senate selection committee expanded five-fold was, he told me, due to party reforms for which he (and Tony Abbott) had long campaigned. In any event those reforms could easily be reversed. That being so I think I am quite correct to refer to “the machine” and to describe this system as being, de facto, a party machine appointments system.

Furthermore, I am fully entitled to describe the wording of the instructions as “deceitful”. That is what they are. The charitable would suggest “misleading” and I agree one could be nice to the Liberal Party’s machine and use that word. I believe, however, in calling a spade a spade. The correct word is “deceitful”. The politicians who constructed that knew perfectly well what they were doing. They were set upon deceiving the voters for the purpose of manipulating them.

The Labor party’s attitude

Above-the-line Senate voting is a bad idea. It is designed to convert a candidate-based system (as required by section 7 of the Constitution) into a party-based system. My reader could say that I am being unduly harsh on the Liberal Party. After all the Labor Party started this with the reforms of the Hawke government in 1984. Should I not attack Labor as fervently as I attack the Liberals? Perhaps I should but I must also acknowledge that I was persuaded by Labor in 1983 and 1984 that the Hawke reforms should be supported.

My clear understanding was that the Hawke reforms were designed to help the great majority of voters to cast an easy formal vote. The reforms of 2016, by contrast, were designed to make it more difficult to vote. There is another reason, however. Labor originally intended to support this system, owned now by the Liberal Party. Along with Victorian Labor Party member and psephologist Chris Curtis I set myself upon a campaign to persuade Labor to oppose the Commonwealth Electoral Amendment Bill 2016. We succeeded.

The problem we have is that we disagree about what a future Labor government should do when it undoes what the Coalition has done. I favour the future theme being the Chifley system – with a variation. He favours the future theme being the Hawke system – with a variation. No doubt exists in my mind that a future Labor government will undo the Coalition’s work, but I suspect it will not implement what I want – nor will it be what Curtis wants! My fear is that a future Labor government will act like “any old” political party. It will place the party’s short-term electoral interests ahead of every other consideration.

While Curtis and I agree that Labor did the right thing to oppose the Commonwealth Electoral Amendment Bill 2016 it should be mentioned that there are plenty of Labor people who think the party made a mistake to do as we requested – and they have a point. One of those is Andrew Giles, member for Scullin (Victoria), who explained it in a conversation with me in February 2020. Such people do blame me, but they blame former Labor senators Sam Dastyari and Stephen Conroy more. Giles is not the only present federal Labor member who thinks the party made a mistake to listen to me, an outsider. There are others. This is what I say to Labor politicians who express such a view:

Three years ago, there were 26 Labor senators – and today there are still 26 Labor senators. Three years ago, there were nine Greens senators – and today there are still nine for the Greens. However, three years ago there were 30 Coalition senators – but today there are 36. The reason is that back then there were eleven senators on the cross benches, but today there are five. All six cross bench losses have gone to the Liberal Party – exactly as the Liberal Party designed with its pretence of “democratic reform”, which Labor had enough sense to oppose.

Furthermore, consider these voting statistics. The Coalition has 47.4 per cent of the senators (36 out of 76) for a Senate first preference vote of 35.2 per cent in 2016 and 38 per cent in 2019, the 2016 figure being mentioned because there was a half-Senate election for the six-year terms within the double dissolution election for the whole Senate. Coalition winnings of seats compared with first preference votes (its “over-representation”) greatly exceeds benefits to Labor or the Greens in that regard.

The Labor politician then recognises that the 2016 changes were not a “democratic reform” but a Liberal Party rig. The tables of my Statistical Appendix illustrate the nature of the rig. There was none in 2010 and 2013 and Table 5 is the exceptional case. It deals with a Senate general election, so the seats were distributed fairly between parties in 2016. The rig is illustrated by the subsequent tables that illustrate the present situation.

How the AEC has handled recent elections

There is another institution to which my attitudes have been very mixed, the Australian Electoral Commission. I don’t want to be hostile to the AEC, but this “independent” body tested me greatly in 2016 and 2019. To make up for the harsh criticisms of the AEC made by me in respect of the 2016 and 2019 Senate elections I have gone over-board in my praise of their handling of by-elections – as I now explain.

When the voter entered the booth, he/she has been greeted with a big sign reading, in very large letters: “Please read the instructions on your ballot paper.” Below that it reads, in much smaller letters: “If you make a mistake, just ask a polling official for another ballot paper.” And below that it reads, in small letters: “Your vote is a valuable thing.” That is fair enough when the instructions give help to voters to cast a formal vote. It cannot be justified when the instructions are there to help the machines of big political parties to manipulate how people vote. Reading the instructions properly does reduce the informal vote for a House of Representatives election where the ballot paper is honest. Not so for the Senate where the ballot paper is dishonest.

Informal voting in Australia is very high by the standards of the world’s democracies. For such a reason it is essential that ballot papers make it crystal clear to voters that vote which counts as formal contrasted to that vote which is not counted because it is rejected as informal. I have tried to explain that to politicians. However, during the 45th Parliament (2016 to 2019) the federal Joint Standing Committee on Electoral Matters did everything it could to shut me up. For details readers are invited to visit my website at www.malcolmmackerras.com. See the chapter “Extreme Vetting”.

I tried a different tactic during the 46th Parliament, elected in May 2019. My submission was short – and to the point. It was the sixth published on the JSCEM website out of 140. Although I expected the Committee to ignore me, I made a point of ensuring that the Electoral Commissioner, Tom Rogers, would know of my concerns. He and his staff have been very helpful.

My letter to the JSCEM was dated 22 August 2019 and began with this sentence: “The worst aspect of the dishonesty of the Senate voting system is the simple fact thar the politicians have had the effect of making the Australian Electoral Commission dishonest in their wake.” To justify that claim I tabled the AEC document sent to every household. It was titled Your official guide to the 2019 federal election: Saturday 18 May 2019. It tells the reader: “If you choose to vote above the line, you need to number at least 6 boxes” (Emphasis is in the original). My comment was: “That statement is a lie.” Does anyone seriously dispute my description? Dealing with the below-the-line vote I recorded that the guide has this:

If you choose to vote below the line, you need to number at least 12 boxes from 1 to 12, for individual candidates in the order of your choice. You can continue to place numbers in the order of your choice in as many boxes below the line as you like.

Again, emphasis is in the original. I recorded then how that would read if the politicians were honest with voters. It should read:

If you choose to vote below the line, you need to number at least 6 boxes, from 1 to 6, for individual candidates in the order of your choice. You can continue to place numbers in the order of your choice in as many boxes below the line as you like. Your vote will only be rendered informal if you fail to number 6 boxes in consecutive order.

At no stage did the JSCEM ask me to appear before them to tell them truths they did not want to hear. However, the Electoral Commissioner, Rogers, has taken notice. I venture to predict that the autumn 2022 federal election will see the official guide revised. It will include (in the fine print) the fact that a single first preference above-the-line will be counted as a formal vote for the party’s candidates. Likewise, six preferences for candidates below the line.

I decided to wage my own education campaign in 2019. I asked friends, neighbours and relatives to question polling officials on this point. A neighbour down the road, a conservative Catholic who always votes for the Liberal Party, as does her husband, voted at the Campbell Public School polling place. The official gave her the two ballot papers as well as the “education” spiel required by the AEC. It went something like this:

For the Senate you need to number one to at least six above the line but you can go beyond that if you like. Below the line you must number from one to at least 12 but you can go beyond that if you like.

To such a spiel Angela reported she had been told on good authority that she need only give a single first preference above the line and it would count as a formal vote. The official said: “You are not supposed to do that”. Angela: “I don’t care what I’m supposed to do. I want to vote for Zed Seselja and the Liberal Party in Group A and I don’t want to vote for any of the other rubbish on this ballot paper if I don’t have to. Have I been informed correctly?” The official conceded she had been informed correctly. She voted accordingly. Her husband cast the same vote at a different time and place.

A very conservative Sydney friend went to the Paddington Town Hall to vote. The official did for him what the Campbell official did for Angela. My friend asked whether he had been informed correctly that a vote for eight candidates below the line was formal. The official replied: “We are not supposed to tell you so, but that vote would be counted as formal.” He gave his first preference vote to Senator Jim Molan, his second, third, fourth, fifth and sixth preferences to the other Coalition candidates and then marked two more squares. They were 7 for Sophie York of Australian Conservatives and 8 for Riccardo Bosi, also of Australian Conservatives. His vote was one of the 137,325 first preferences for Molan who, of course, was defeated. Molan was the only senator to get any benefit from that vote. The other five Coalition candidates were not incumbents and the Australian Conservatives never had any hope.

A Labor-supporting Sydney friend went to the Balmain Town Hall polling place where he received the same spiel as was given to the others. After a similar conversation the official gave him an immediate affirmative answer: “That vote would be fully counted as formal with your first preference deemed to be for Tony Sheldon, second for Tim Ayres, third for Jason Yat-Sen Lee, fourth for Simonne Pengelly, fifth for Aruna Chandrala and sixth for Charlie Sheahan” was the answer.

But five other friends/relatives were given the wrong answer. In each case my friend/relative was told quite firmly: “That vote would not be counted because it would be rejected as informal. Just read the instructions. They make it quite clear such a vote would not be valid.” The voters were then pointed to the sign in the booth: “Please read the instructions on your ballot paper.” In each case the voter did what the politicians wanted – they all voted 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 and 6 above the ballot dividing line. Their votes helped the big party machines to get their senators elected in the “correct” order.

I have told Rogers (and a few other AEC officials) several times that it is the duty of the AEC to help voters, not big party machines seeking voter manipulation. Ideally, every voter should be told the truth, the whole truth and nothing but the truth. I hope that will be the AEC policy at the upcoming third election under this outlandish system.

The AEC did not design the system. For that the politicians should get the blame – as should their spin doctors. While the task of the AEC is difficult, I hope – and expect - its performance will improve, until this system is done away with, as a result of which no problem would the arise. Under a decent system there should be no problem about educating voters. There has been a problem under the present system because the politicians who concocted the Senate ballot paper have been so determined to manipulate the voters. Rogers has thus far not been able to understand quite how shocking is the idea that his officers should help the manipulators when they should be helping the voters. Every polling official should be instructed to tell the truth to voters when asked. So far as practicable the signs “Please reads the instructions on your ballot paper” should be kept in cold storage as Australia waits for the politicians to design and implement a decent Senate voting system.

The Senate voting system in operation for the 2016 and 2019 elections (and which will operate again at the 2022 election) is very dishonest and very defective. The extraordinary thing, however, is that the general public does not understand that it is so dishonest. An important part of the reason for that has been the willingness of the AEC to legitimise it as the above stories show.

There are two other explanations. One is the willingness of the various parties to co-operate with the system. They do that by handing out “how to vote” material that assumes the voter should vote according to the instructions on the ballot paper. Just as important is the willingness of the new method’s spin doctors to explain the system as though it were constructed according to genuine democratic principles. That it is not so constructed is explained in my next section.

The propaganda that denounced Ricky Muir – and destroyed the Hawke system

The half-Senate elections to fill vacancies beginning on 1 July 2014 took place in two stages. For seven eastern jurisdictions the date was 7 September 2013. That also included the election of six senators for Western Australia, but that was voided so the Western Australian re-election occurred 0n 5 April 2014.

In respect of the September 2013 Senate elections instant commentary by gurus such as Antony Green created the impression of a large Senate cross bench from 1 July 2014 composed almost entirely from members of so-called “micro parties” getting elected by “gaming the system”. The distinguished “preference whisperer” Glenn Druery became a hate figure because he organised all this alleged negation of Australian democracy. According to election-night propaganda there were five incoming senators who would be elected by this process. They were David Leyonhjelm (NSW), Ricky Muir (Victoria), Jacquie Lambie (Tasmania), Bob Day (South Australia) and Wayne Dropulich (Western Australia). Lambie was elected as a candidate of the Palmer United Party while Leyonhjelm came from the Liberal Democrats and Day from the Family First Party.

It is true that none of the above secured a quota on the first count. They all needed preferences. However, Leyonhjelm, Lambie and Day received respectable first preference numbers and I was able quickly to demonstrate that the election of those three was nothing unusual. I did that in a thirteen-page document titled In Defence of the Present Australian Senate Electoral System published in November 2013 by the Public Policy Institute of the Australian Catholic University.

Therefore, the only two cases remaining to be classified were those of Muir and Dropulich. In his document Submission to the Victorian Parliament’s Electoral Matters Committee Inquiry into the Conduct of the 2018 Victorian State Election Antony Green wrote this on page 9 dealing with the 2013 Senate election:

Under group voting tickets at the 2013 election, a quarter of the Senators elected were from trailing positions, and the ratio of parties passed to trailing wins was much higher than at any previous election. In Western Australia, Wayne Dropulich of the Australian Sports Party was elected despite the party polling just 0.23 percent or 0.016 quotas. The Sports Party finished 21st of 27 parties on first preferences, but received ticket preferences from 20 different parties to achieve a quota, 15 of those parties having polled a higher first preference vote. Preferences allowed Dropulich to leap-frog parties and defeat a Labor candidate who began the count with a remainder of 0.86 quotas. In Victoria, Ricky Muir and the Australian Motoring Enthusiasts Party began the count with 0.51 percent or 0.035 quotas, receiving preferences from 22 other parties including nine with more votes, and passed a Liberal candidate who began the count with 0.81 quotas.

My objection to that is to Green’s failure to mention that Dropulich was never validly elected and never became a senator. At the re-election on 5 April 2014 senators easily elected were Liberals David Johnston, Michaelia Cash and Linda Reynolds, Labor’s Joe Bullock, and Scott Ludlam of the Greens. Johnston, Bullock and Ludlam were elected with a quota on the first count. The minor party that won a seat was the Palmer United Party. Its candidate, Zhenya Wang, scored 156,352 first preference votes and easily reached the quota of 182,544 votes after full preference distribution. It is difficult to see anything wrong with Wang’s election.

So, the upshot was that at the 2013/14 Senate elections forty senators were elected of which thirty-nine should not have been used as an argument to support the Commonwealth Electoral Amendment Act 2016. Muir was the exception. His election did raise eyebrows. The propaganda arising from his election was what enabled the new system to be installed in 2016. At the July 2016 election he lost his seat. Lambie, Leyonhjelm and Day were re-elected.

It is, however, desirable to distinguish the cases of the three re-elected senators. Lambie began as a protégé of Clive Palmer but quickly became an independent. She has become a permanent fixture in the Senate. After a short-term interruption to her career at the hands of the High Court in the “citizenship crisis” she was elected again in May 2019 and is serving a six-year term beginning on 1 July 2019 and expiring on 30 June 2025. This will be her first six-year term. On the other hand, Leyonhjelm and Day did not last long as twice-elected senators. Leyonhjelm resigned his Senate seat early in 2019 to contest the March 2019 New South Wales election at which he was unsuccessful. Day lost his Senate position in November 2016 due to disqualification. HIs seat was filled by recount of votes on Thursday 13 April 2017. The second Family First candidate, Lucy Gichuhi, won the seat with 69,442 votes compared with 65,841 for Labor’s Anne McEwen. Gichuhu became the first black African member elected to any Australian house of parliament.

Late in April 2017 the Family First Party folded up and Gichuhi became an independent. In February 2018 she joined the Liberal Party. She hoped to get a winnable position on the Liberal ticket for the May 2019 election – but was given the fourth position by the pre-selection committee meeting in June 2018. The four-person ticket consisted of Senator Anne Ruston in first place, Senator David Fawcett second, non-incumbent Mt Alex Antic third and Gichuhi in fourth place. Unlike Molan she did not campaign for a below-the-line vote. She knew the system well enough to know it is so rigged as to give senators like her no chance to be re-elected.

That Ricky Muir was the only senator elected in 2013/14 through the work of a “preference whisperer” is easily demonstrated. The allegation that the new cross bench was composed almost entirely of “micro parties gaming the system” led to an inquiry by the federal Joint Standing Committee on Electoral Matters (JSCEM) which reported in May 2014. Its Interim report on the Inquiry into the conduct of the 2013 Federal Election: Senate voting practices made the allegation but could find only one case of it. In the Introduction this statement is made in the second and third paragraphs:

The Senate voting system has come under intense scrutiny following the 2013 election. In Victoria the Australian Motoring Enthusiast Party representative was elected to the Senate having received only 0.51 per cent of the formal first preference votes. . .

The Motoring Enthusiast Party received only a total of 17,122 votes in Victoria, equalling just 0.0354 of a quota. However, through manipulation of preference deals, the party was elected to the final seat with a transfer of 143,118 votes from the Sex Party, whose transferred votes themselves had been transferred from over twenty other parties, arguably coming from voters that had no idea that their vote would elect a candidate from such an unrelated party with such low support.

My reader may wonder why the above quotation is broken. The reason is that the omitted section refers to Western Australia. That information is wholly irrelevant to the argument. It does not in any way undermine my view on the election of six senators for Western Australia to serve terms beginning on 1 July 2014. The result of that election was not in any way influenced by preference whispering. Quite simply it was the obvious result reflecting the will of the voters of Western Australia.

Action arising from the interim report

The recommendation of the interim report was for optional preferential voting above the line and for partial optional preferential voting below the line with six preferences required for a formal vote.

Had that report been adopted the divided ballot paper would have read: “You may vote by” together with “either” and “or”. The above-the-line statement would have read: “Either, placing the number 1 in the box above the group of your choice. You can show more choices if you want to by placing numbers in the other boxes starting with the number 2.”

The below-the-line statement would have read: “Or, numbering at least 6 of these boxes in the order of your choice of candidate.”

Tony Abbott was the prime minister at the time. His reaction to the report was to do nothing. It is my belief that, if he had remained prime minister, the next election would have been for the House of Representatives and half the Senate in the late spring of 2016. Instead Malcolm Turnbull replaced Abbott in that office in September 2015 and the next election was a general election for all members of both houses on 2 July 2016.

The positions of Abbott and Turnbull within the Liberal Party were very different. Abbott was comfortable with the party’s socially conservative base. Turnbull was not. Therefore, Turnbull decided to use his strength within the party’s business base. To do that he must be far more vigorous with industrial relations reform than Abbott would have been.

Abbott had secured passage through the House of Representatives of three pieces of industrial relations legislation which were blocked by the Senate. My belief is that he would not have pursued them further during the 44th Parliament. He certainly would not have wanted a winter campaign for the 2016 election. The general basis of my belief is explained in my chapter “Extreme Vetting” that can be found on my website. The particular basis is my description of a conversation I had with Abbott in his Canberra office on the afternoon of Tuesday 16 August 2016.

Anyway, Turnbull decided that he wanted a double dissolution and a July 2016 election. He pursued that objective by creating “triggers” for that double dissolution through Senate rejection of industrial relations legislation. He decided to do that over the period being the summer of December 2015 and January-February 2016. However, when he raised this idea with Liberal Party officials, they warned him that he would suffer a disaster unless he first could fix the Senate electoral system.

Consequently, the Commonwealth Electoral Amendment Bill was presented for parliamentary approval late in February 2016. It would have simply implemented the interim report to the letter. However, there arose certain developments Turnbull had not expected. The main one was that Labor had been persuaded to oppose the very legislation to which its members had assented.

Labor’s position is explained above in my section “The Labor party’s attitude”. In May 2014 its members on the JSCEM put their signatures to the proposed “democratic reform” wanted by the Liberal Party, the Greens and Senator Nick Xenophon. Labor’s change of view, however, changed the course of events. That change placed the Nationals in a critical situation. Its votes had to be secured for the bill. To do that the deceitful instructions to voters had to be inserted.

In my section above titled “Liberal party machine owns the system – and drafted the ballot paper wording” I justify the description “deceitful” in relation to the instructions to voters with this assessment: “the purpose of the wording of those instructions is to deceive the voter into believing that any failure to number the boxes 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 and 6 above the line (or 1 to 12 below the line) would result in that ballot paper being placed in the pile of informal votes.”

That needs elaboration because it should be noted that such was not the original intention of the Liberal Party, the Greens or Xenophon. They had hoped to implement the interim report to the letter. From their point of view, however, Labor and the Nationals were flies in the ointment.

The Nationals were completely comfortable with the Hawke system because it enabled them to contest Senate elections in Western Australia where the Liberal Party had long refused the joint ticket arrangements prevailing in the eastern states. To WA Nationals voters it was explained that any excluded Nationals candidate would see his preferences automatically go to the relevant Liberal candidate still in the count. That would no longer be the case under the interim report’s proposal.

The Nationals demanded one very important concession. The above-the-line instruction must read: “By numbering at least 6 of these boxes in the order of your choice”. That embarrassed the Liberal Party hugely. If those words actually meant what they said Labor would have a field day at their expense. The Labor line would be: “Under our reforms in 1984 we cut the Senate informal vote to one-third of what it had been. You Liberals want to triple it, restore it to what it had been under Menzies and Fraser.”

So, the compromise was reached whereby the instructions wanted by the Nationals were inserted subject to so-called “savings provisions” whereby a single first preference above the line would be required by law to be counted as a formal vote. The supporters of the new system were happy to see some increase in the informal vote as a result of their legislation, but they avoided what they dreaded: a massive rise in the informal vote that would deeply embarrass them.

The upshot was that the Senate ballot paper now has four contrivances none of which can be justified according to any democratic principle. The four contrivances are the thick black line that runs through the ballot paper, the party boxes above that ballot paper dividing line, the deceitful instructions for the above-the-line vote and the deceitful instructions for the below-the-line vote. I am, therefore, entirely justified in asserting that the Liberal Party, the Nationals, the Greens and Xenophon gave the Australian people the worst-ever Senate voting system. I am also entirely justified in describing the system as one of voter-manipulative proportional representation.

But is not the system semi-proportional?

The answer to the above question lies in the affirmative. This system is unfair to voters, unfair between candidates and unfair between parties. The explanation for this third unfairness is that the system is semi-proportional, not one of proportional representation between parties. The reason for that is this piece of analysis: district magnitude six is inherently unsatisfactory. It should be an odd number, either five or seven. Selling to politicians the idea of district magnitude seven is very easy – as I now explain. If the size of the Senate is increased from 76 to 88 then the size of the House of Representatives would rise from 151 to 174 or 175. The reason for that is the requirement of section 24 of the Constitution that the number of members of the House of Representatives shall be, as nearly as practicable, twice the number of senators. That is popularly known as the “nexus” provision.

Whether parties of the left or parties of the right have a Senate majority does not depend on majorities being gained in a majority of states. It depends upon one side or the other getting 57.2 per cent of the vote (after preferences) in a single state at back-to-back elections. In the present 46th Parliament parties of the right have a Senate majority due to Queensland voters rejecting the left in both July 2016 and again in May 2019. At both half-Senate elections, the Liberal National Party won three of six senators. At both elections, Pauline Hanson’s One Nation won a seat, Hanson in 2016 and Malcolm Roberts in 2019. So, combined they have eight out of the twelve Queensland senators.

In 2016 Labor won two Queensland seats, the Greens none. In 2019 Labor and Greens each won a single seat, giving Larissa Waters a six-year term. She previously had a six-year term from 1 July 2011, but it was cut short by the 2016 double dissolution. She was elected again in 2016 – but only to a three-year term. So, combined parties of the left have four, three Labor and Waters from the Greens.

During the 41st Parliament the Howard government enjoyed a Senate majority – which it proceeded to abuse by enacting Howard’s infamous “work choices” legislation. That majority was obtained by the Coalition securing only 41.8 per cent of the Senate vote in 2001 and 45.1 per cent in 2004. In 2001 the Coalition was able to win eighteen of the thirty-six long-term Senate places, 50 per cent, with only that 41.8 per cent vote. In 2004 the result in Queensland was three for Liberals and one for Nationals (Barnaby Joyce), or 66.7 per cent of seats for 58 per cent of votes after preferences. That gave the Coalition twenty-one of the forty seats contested, 52.5 per cent of seats for 45.1 per cent of votes. The Coalition thus had 39 senators to 37 for the combination of everybody else.

During the 43rd Parliament (Julia Gillard’s term) the combined parties of the left had a Senate majority. The results in Tasmania in November 2007 and August 2010 are the explanation. Tasmanian voters rejected the Liberal Party at those back-to-back elections by the same margins as Queensland voters rejected parties of the left in 2016 and 2019. At each election the Tasmanian result was three Labor and one for the Greens, four out of six. So, the Labor-Greens total combination was 39 senators.

Justifying an increase in the size of federal parliament

It is commonly asserted that it would be politically very difficult to sell to the general public the idea of an increase in the number of federal politicians. That is a notion I reject completely. All that is needed is the political will to do it. Once the will is there and the numbers can be obtained the increase occurs, and the public then accepts the result because the decision enjoys third-party validation. By “third-party validation” I mean not merely smaller parties but also the commentariat which includes journalists and independent psephologists like yours truly, Antony Green, Kevin Bonham, George Williams, Chris Curtis and the Proportional Representation Society of Australia (PRSA).

In my case the full reasoning is set forth in my chapter “Increasing the Size of Parliament” that can be found on my website. The arguments I present are comprehensive and cover all aspects of the subject. In the past the problem I have seen has been persuading the government of the day to do it. However, I believe that problem is receding. Instinct tells me so but there is another straw in the wind that I now explain.

The federal Joint Standing Committee on Electoral Matters (JSCEM) publishes a report on each federal general election following that election. The report in question excites my hostility more often than my approval but the most recent is interesting. Titled Report on the conduct of the 2019 federal election and matters related thereto it was published in Canberra in December 2020. It comes to 206 pages. Anyway, it happened that, even as I was doing the maths needed for my satisfaction on this subject there appeared on page 163 this Recommendation 24:

The Committee recommends that consideration be given to a future constitutional referendum to break the nexus between the number of Senators for the States and the number of Members of the House of Representatives.

That was preceded, on page 160, by a table showing the average number of electors per federal member at 66,664 in 1984 (with 148 members) and 108,770 in 2019 (with 151 members). Those numbers are quite close to mine. Also shown are some outdated numbers for the United Kingdom and Canada and irrelevant numbers for New Zealand. The outdated British electorate number for 2019 is 47,074,800, an average for 650 members of 72,423. The outdated 2015 Canadian electorate number was 25,939,742, an average for 338 members of 76,745. Those British and Canadian numbers are also quite close to mine. In Canada’s case the 2015 numbers are identical to mine but the average for 2015 of 76,745 grew to 80,985 for the October 2019 Canadian general election. I do not yet have the numbers for the Canadian general election held on 20 September 2021.

The rest of page 160 and the whole of pages 161 and 162 are devoted to arguing that there is a good case for increasing the size of the House of Representatives and a good case for keeping the number of senators at 76.

On page 162 paragraph 8.60 reads:

The number of voters per Member of Parliament is growing to an extent where it is challenging for members to service constituent workloads. Accordingly, at an appropriate time, there will need to be an increase in the number of members of the House of Representatives

Also, on page 162 paragraph 8.61 reads:

The number of office suites in the Parliamentary building and the space for seating on the floor of the House Chamber are suitable for accommodating future growth in the number of MPs.

Again, on page 162 is paragraph 8.62 that reads:

However, there is no equivalent case to expand the number of Senators, as their primary duties pertain to legislative work rather than constituent work. Australia’s population has now reached the juncture where the House needs to grow further to keep pace. But the Senate does not need to enlarge, and doing so could make it more fragmented and thereby complicate the ability to achieve compromise in the chamber on legislation.

My massive dissent is recorded here. To give the Australian people a decent Senate voting system it is essential that the number of senators for each state be increased from 12 to 14 – to create half-Senate elections for seven senators, an odd number. That would increase the size from 76 to 88. A by-product of that would be to increase the size of the House of Representatives by approximately 24 members. In addition, however, I would increase the number of senators for territories from two to three so there would be a total of 90 senators.

Finally, I give a summary of what each mainland state would get out of the increase I propose. I write “mainland state” because there are three privileged jurisdictions at present, Tasmania, the Australian Capital Territory and the Northern Territory. They would get no increase in their numbers in the House of Representatives, presently being five, three and two members, respectively.

New South Wales would go from the present 47 to 55, so eight more members. Victoria would go from the present 38 (46th Parliament) to 45, so seven more members. Queensland would go from the present 30 to 35, so five more embers. Western Australia would go from the present 16 (46th Parliament) to 18, so two more members. South Australia would go from the present 10 to 12, so two more members. The total size of the House of Representatives would rise from 151 to 175, so 24 more members.

Some details of my case are set out in Tables 11, 12 and 13 of my Statistical Appendix. The remaining details can be inspected by visiting my website.

Does above-the-line voting conform to the Constitution?

There was a time when I fully accepted above-the-line voting for the Senate. The reason for my acceptance was a foolish application of the precept “Never let the perfect be the enemy of the good”. The Labor Party had established in my mind that there was a need to bring about a substantial reduction in the Senate informal vote. The above-the-line way of doing it was condemned by the PRSA and I listened to their views but decided that, for a variety of reasons, above-the-line voting was the only practical option whereby the informal vote could be substantially reduced. The “perfect” solution (partial optional preferential voting in candidate-based elections) had to give way to the “good” – helping substantial numbers of voters to cast an easy formal vote.

Above-the-line voting began in 1984 but in 1990 the scales fell off my eyes and I now denounce it for the Senate. It is clearly a device to circumvent the requirements of section 7 of the Australian Constitution:

The Senate shall be composed of senators for each State, directly chosen by the people of the State, voting, until the Parliament otherwise provides, as one electorate. . .

The commandment it clearly violates is that senators shall be directly chosen by the people.

In 1990 the PRSA succeeded in their campaign to persuade me that the above-the-line voting “option” was a bad idea, but I later came to the view that it can be justified in some cases of high district magnitude. The PRSA view has always been that above-the-line voting is unequivocally a bad idea. I have never been a member of the PRSA though, in recent times, I have become a fellow traveller. The PRSA and I are at one in asserting that every PR system should be made as democratically respectable as possible.

This conversion caused me to consider again the McKenzie case decided by Chief Justice Sir Harry Gibbs in November 1984. Cyril John McKenzie was an ungrouped candidate for Queensland at the election of seven senators for each state held on Saturday 1 December 1984, the first election under the Hawke system. He received 86 votes. In conducting the case himself he did a very good job – without any help from barristers! He told Sir Harry of his view that the system mightily offended his democratic principles when a first preference vote for Senator Margaret Reynolds, Senator David McGibbon or Senator Ron Boswell could be recorded by placing a single 1 above the line in the square for the Labor (Reynolds), Liberal (McGibbon) or National (Boswell) parties - but to vote for McKenzie required the voter to number all squares consecutively from 1 to 28.

As indicated above I wanted the Hawke system to succeed at that time. I took no interest in the case though I heard that those who attended hearings thought McKenzie conducted his case very well. It did not occur to me to think McKenzie might win. Nor did it occur to me to think that the day would come when I would arrive at my present view: the McKenzie case was wrongly decided.

The decision was handed down on Tuesday 27 November 1984, just five days before polling. Two paragraphs are worth quoting:

2. The plaintiff argued his own case and did so very clearly. The submissions which he has made are understandable and by no means irrational. The provisions which he seeks to have declared invalid are of recent origin and, so he contends, place him, as a candidate who belongs to no political party, at a disadvantage in his bid for election.

Later comes Sir Harry’s critical paragraph:

8. In my opinion, it cannot be said that any disadvantage caused by the sections of the Act now in question to candidates who are not members of parties or groups so offends democratic principles as to render the sections beyond the power of the Parliament to enact. . .

In other words, these provisions are very offensive to the democratic values of the Constitution, but Gibbs was able to say not SO offensive as would lead him to strike down next Saturday’s election. For political reasons, therefore, the High Court ruled that an election could be regarded as a direct election if a direct election option is available to the voter. The politicians could rig that option to their heart’s content and the High Court would still say that is okay.

There is another part of the judgment that needs contesting. Gibbs wrote: “It is right to say that the electors voting at a Senate election must vote for individual candidates whom they wish to choose as senators but it is not right to say that the Constitution forbids the use of a system which enables the elector to vote for individual candidates by reference to a group or ticket.”

The ridiculous nature of that comment can be seen by looking at the origin of the words “directly chosen by the people” as found in sections 7 and 24 of the Australian Constitution. Those words go back to the northern summer of 1787 at Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. In that city in that year, meeting from May to September, the Founding Fathers of the USA drew up their Constitution. There were a few democrats among them but not many. Consequently, they decided that the Presidency, the Senate and the Supreme Court should not be democratic institutions. Where the democrats won was in respect of the House of Representatives. Thus, in the very first article there is a section 2 which commands: “The House of Representatives shall be composed of Members chosen every second Year by the People of the several States, and the Electors in each State shall have the Qualifications requisite for Electors of the most numerous Branch of the State Legislature.” Australia’s Founding Fathers were much better democrats than America’s and they had the advantage of more than a century elapsing between their American equivalents and their good selves. Having noticed the anti-democratic tricks to which politicians get up they were determined to prevent our Commonwealth Parliament from implementing such tricks. Determined to ensure that Australian federal electoral systems always be CANDIDATE-BASED they caused the Australian words to be “DIRECTLY chosen by the people” where the American words were merely “chosen by the people.”

Back in 1984 I merely watched the McKenzie case from afar. Not so the second case which was driven by my wish to see McKenzie over-turned. I wanted the Commonwealth Electoral Amendment Act 2016 ruled to be unconstitutional, so I sought to persuade a Senate cross bencher to take it to the Court. I succeeded with South Australian Family First Senator Bob Day. He persuaded the Tasmanian Family First lead candidate Peter Madden to join him in the case. At no stage did I give Day any assurance that he would win. For him politically, however, I expressed the view that his prominence in the matter would help him get re-elected. He was successful in that quest.

The official title of the case is Day v Australian Electoral Officer for the State of South Australia: Madden v Australian Electoral Officer for the State of Tasmania (2016) HCA 20: S77/2016 and S109/2016. It was handed down on Friday 13 May 2016, four days after the double dissolution was put into effect on Monday 9 May 2016. The decision upheld the constitutional validity of legislation passed through both houses of Parliament on the afternoon of Friday 18 March 2016. Just as McKenzie is known by its short name so this case is generally known as Day and Madden.